The language of the Internet

In my previous post I tried to better understand exactly what is the Internet, how its constructed, along with the technologies and protocols used, and specifically how do these things all work together to allow billions of devices spread throughout the globe to communicate with one another. What I learned is that the Internet isn't really a single technology or protocol, but actually a multilevel stack of protocols, each with a specific focus and largely ignorant of the layers, multiple levels above and below.

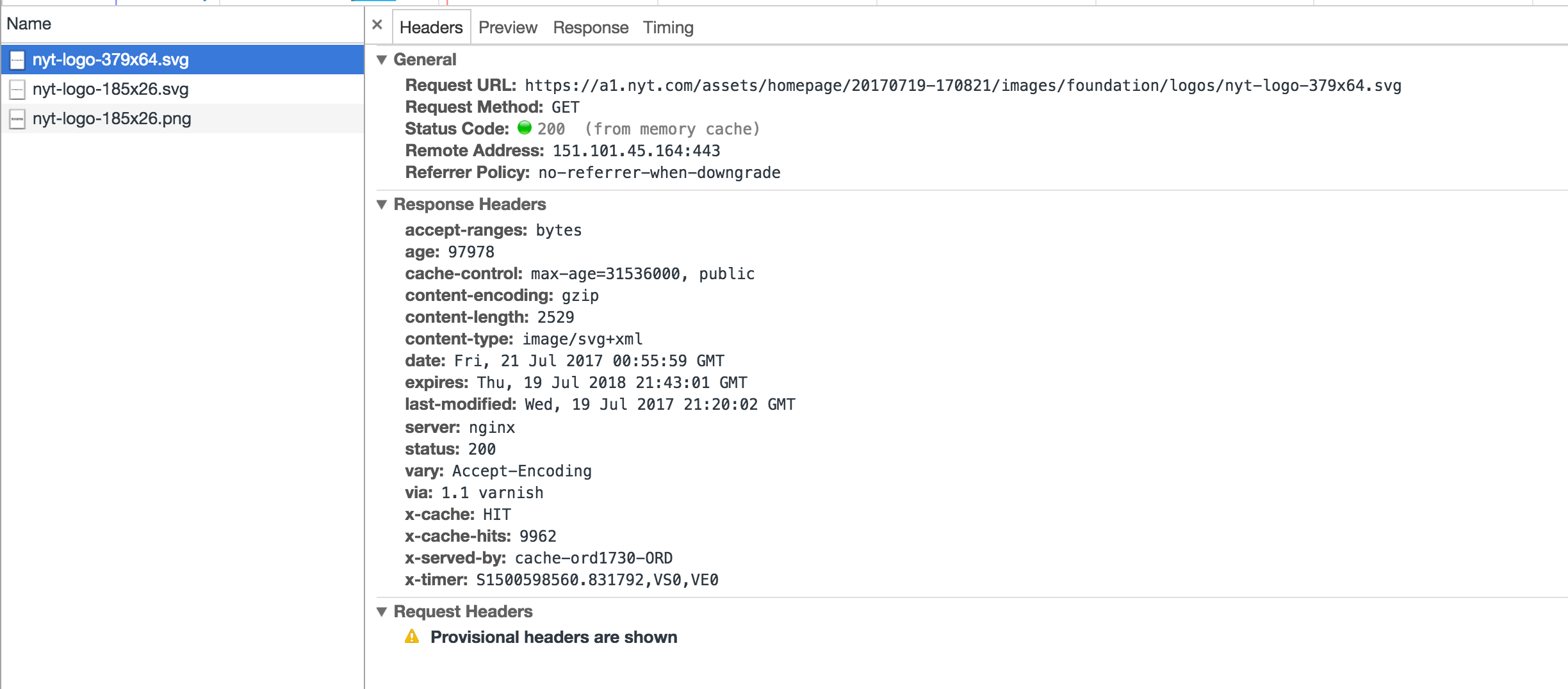

As developers we spend much of our time at the very top level of the Internet protocol stack, which is called the Application Layer. Like the name suggests the Application Layer protocols are focused on how applications should communicate with one another. Some of the more popular application layer protocols are: FTP, IMAP, and BitTorrent, however by far the most popular protocol is HTTP. If I open my browser and visit a site like nytimes.com, using the Chrome DevTools Network tab we can see a couple hundred HTTP requests get fired off immediately.

If I inspect one of these requests I can see that it's just a plain text message that appears to be asking a server for a specific image. When I was first learning about HTTP this was somewhat surprising to me. Virtually all of the communication on the Internet is done using this very simple, human readable message format.

There is nothing special about what the browser is doing. I can construct

similar requests manually using a tool like telnet. Below I establish a TCP

connection with the nytimes.com server on port 80 and send the message "hi".

The server then responds with HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request to let me know that

"hi" is meaningless to it.

~ » telnet nytimes.com 80

Trying 151.101.193.164...

Connected to nytimes.com.

Escape character is '^]'.

hi

HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

Connection closed by foreign host.

However, if I'm a little more specific about what I want and speak in HTTP rather than English I can manually ask the server for specific resources

~ » telnet nytimes.com 80

Trying 151.101.193.164...

Connected to nytimes.com.

Escape character is '^]'.

GET https://a1.nyt.com/assets/homepage/20170719-170821/images/foundation/logos/nyt-logo-379x64.svg

Host: a1.nyt.com

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: nginx

Content-Type: image/svg+xml

Last-Modified: Wed, 19 Jul 2017 21:20:03 GMT

Expires: Thu, 19 Jul 2018 22:25:05 GMT

Cache-Control: max-age=31536000, public

Content-Length: 6309

Accept-Ranges: bytes

Date: Fri, 21 Jul 2017 14:56:31 GMT

Via: 1.1 varnish

Age: 145886

Connection: close

X-Served-By: cache-ord1720-ORD

X-Cache: HIT

X-Cache-Hits: 1

X-Timer: S1500648991.434743,VS0,VE0

Vary: Accept-Encoding

....

This time I asked the server for a specific image (the nytimes logo) located at

a specific host, and the server responds with a 200 OK to let me know that it

understood my request and was able to fulfill it. It also sends some additional

information in the form of headers, which describe the type of content that

is sent, the date, how long to cache the file, and finally after the headers

the response body which is the binary representation of the image.

The first time that I saw this I was a little shocked that this simple protocol was the workhorse of one of the world's most dynamic and complex systems. But that's it, this is how most of the applications on the Internet communicate with one another.

What is HTTP

HTTP is transmitted via a sequence of exchanges between a client and a server called a HTTP session. For a typical session a server will be listening for TCP connections on a specific port, the client will attempt to establish a TCP connection with the server, and if successful submit its request to the server. The server will then respond and potentially close the connection.

Once a connection is established all communication is conducted in HTTP. HTTP is a request / response protocol composed of two distinct message types. The first type of message is a HTTP request. The client sends this message to a server and formats it so that the server can interpret the request. The server then responds with the second type of message, the HTTP response. This message is formatted in a way such that the client can understand it. The specification for the formatting of these messages is governed by the HTTP 1.1 specification.

The specification itself is of course very detailed governing things such as the proper number of spaces between fields, character sequences used for message termination, allowed characters, and other minutiae. However, most of the important information in a HTTP message occurs in the first few lines.

The typical request line will look like below

Request-Line = Method Request-URI HTTP-Version

The Method corresponds to a list of allowable HTTP actions: OPTIONS, GET,

HEAD, POST, PUT, DELETE, or CONNECT. The most common actions are either GET

(retrieve a resource), or POST (update a resource).

The Request-URI tells the server which resource the client's request applies

to. So in my manual nytimes request above I was telling the server to apply my

GET request to

a1.nyt.com/assets/homepage/20170719-170821/images/foundation/logos/nyt-logo-379x64.svg.

The final field, the HTTP-Version lets the server know which version of HTTP the client message is using.

The sever then responds using a very similar message format, where the first line follows the specification below.

Status-Line = HTTP-Version SP Status-Code SP Reason-Phrase CRLF

Again, HTTP-Version lets the client know which version of HTTP that the server is

using, while the final two fields are a numeric machine readable Status-Code,

and human readable equivalent Reason-Phrase.

There are many details not covered above, specifically a multitude of potential headers, but these largely function as metadata that can be used to transmit the data more efficiently, or help browsers cache files to improve performance. In summary, the bulk of the messaging protocol that powers the Internet boils down to a few human readable lines of text.