A little while ago one of the other apprentices posted the Clojure code below in Slack and asked if anyone had a good explanation for why it worked. If it’s not clear from the function name, this function finds the greatest common divisor for a pair of integers.

(defn gcd [n1 n2]

(if (zero? n2)

n1

(gcd n2 (mod n1 n2))))

I honestly hadn’t seen this particular algorithm before and it wasn’t immediately obvious to me why it would work. A quick google search led me to the Wikipedia page for Euclid’s Algorithm.

Euclid's algorithm provides an efficient way to find the greatest common divisor for two integers. The naive algorithm for finding the GCD of two integers would be to first generate the prime factorization of both integers, and then find all of the shared prime factors and take their product.

For example, the prime factorizations of 36 and 156 are:

\begin{align*} 36 &= 2 * 2 * 3 * 3 \newline 156 &= 2 * 2 * 3 * 13 \end{align*}

The common prime factors of 36 and 156 are 2, 2, and 3, so the GCD is \( 2 * 2 * 3 = 12 \).

However, finding the prime factors of large integers is a very difficult problem. Euclid's algorithm efficiently finds the GCD without requiring the prime factorization, which is a big advantage over the naive approach especially for large integers.

The algorithm

Euclid's algorithm works as follows. First, it's initialized with the two integers \( a \) and \( b \) that we want to find the GCD for (where \( b \) is the smaller of the two integers). We then divide \( a \) by \( b \), if the remainder is not zero then the process is repeated, except now \( b \) is used in place of \( a \) and the remainder of \( \frac{a}{b} \) is used in place of \( b \). This process continues until the remainder is zero at which point the last nonzero remainder \( r_{n-1} \) is declared the GCD of \( a \) and \( b \).

\begin{align*} GCD(a, b) &= GCD(b, r_1) \newline &=GCD(r_1, r_2) \newline &=GCD(r_2, r_3) \newline &\vdots \newline &=GCD(r_{n-3}, r_{n-2}) \newline &=GCD(r_{n-2}, r_{n-1}) \newline &=GCD(r_{n-1}, 0) \quad * \text{stop the algorithm } r_{n-1} \text{is the GCD} \newline \end{align*}

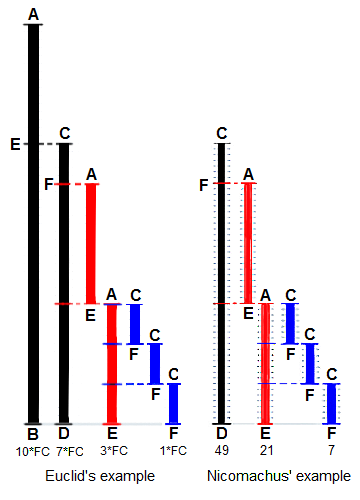

The Wikipedia page provides a good overview of the algorithm, and has several nice visualizations like the one below that attempt to explain the algorithm.

While the visualizations provide a nice representation as to how the algorithm works, I didn't think they really explained why it works.

An old coworker told me that his first step after encountering a new technical concept is to do the following google search: intuition + technical concept. I thought this was a brilliant suggestion and always do this now, but in this case the search intuition Euclid’s Algorithm didn’t turn up much. Most of the “intuitive” explanations were just restatements of the proof. Generally, I think most technical disciplines are overly quick to resort to mathematical notation. However, in some cases a proof really is the only way to understand exactly what is going on. I think this is probably one of those cases, as I couldn't really find a good intuitive explanation as to why this algorithm would work.

Why Euclid's algorithm works

The proof on Wikipedia is pretty clear, but I felt like it hid the core of the argument in the middle of the final paragraph, so I wanted to try to expand on it a bit to help convince myself why this works.

First, consider how we're generating the remainders. As the initial step, we divide \( a \) by \( b \) and then as long as the remainder is not zero, we use \( b \) and the remainder of \( \frac{a}{b} \), \( r \) as the arguments for the next step.

Another way of describing this process is we represent \( a \) as:

\begin{align*} &a = bq + r \newline &\text{where } 0 \leq r < |b| \end{align*}

if \( r = 0 \) stop and the previous remainder is the GCD, otherwise use \( b \) and \( r \) as the arguments for the next step in the algorithm.

For example, if \( a=156 \) and \( b=36 \) then we can write \( a \) as:

[ 156 = 36*4 + 12 ]

with \( q=4 \) and \( r=12 \), since \( r \) is not zero we repeat this process using \( b \) in place of \( a \) and \( r \) in place of \( b \)

[ 36 = 12 * 3 + 0. ]

\( r \) is now zero, so we stop and 12 is the GCD.

The Division Theorem actually guarantees that for any two integers such a representation exists. One thing to notice is that the remainder is strictly less than \( b \) and greater than or equal to zero, so the sequence of remainders generated by Euclid's algorithm is strictly decreasing and bounded below by zero. This gives us confidence that the algorithm will eventually terminate.

The second and probably the most important property for understanding why Euclid's algorithm works is that when \( a = bq + r \) the set of common divisors for \( a \) and \( b \) is the same as the set of common divisors for \( b \) and \( r \).

We can see this by first assuming \( d_1 \) divides \( a \) and \( b \). If \( d_1 \) divides \( a \) and \( b \) then \( d_1 \) also divides \( (a - bq) \), since \( d_1 \) is a factor of both \( a \) and \( b \), which implies that \( d_1 \) divides \( r \) since \( (a - bq) = r \).

Similarly, assume \( d_2 \) divides \( r \) and \( b \). If \( d_2 \) divides \( r \) and \( b \) it also divides \( (bq + r) \), since \( d_2 \) is a factor of both \( b \) and \( r \), which also implies that \( d_2 \) divides \( a \) since \( (bq + r) = a \).

Therefore, any divisor of \( a \) and \( b \) will also be a divisor of the remainder \( r \) and likewise a divisor of \( b \) and \( r \) will also be a divisor of \( a \). One such divisor is the \( GCD(a,b) \), so the \( GDC(a,b) = GCD(b,r) \).

Since we've proved \( GCD(a,b) = GCD(b,r_1) \), rather than looking for \( GCD(a,b) \) we can look for \( GCD(b,r_1) \) and since \( GCD(b,r_1) = GCD(r_1,r_2) \), rather looking for \( GCD(b,r_1) \) we can look for \( GCD(r_1, r_2) \) .... and so on until \( GCD(r_{n-1}, 0) \) at which point we've found \( GCD(a, b) \). Additionally, we know this sequence of remainders will eventually terminate since the remainders are decreasing and bounded below by zero.

I still don't think this is a particularly intuitive algorithm, but working through the proof helped me to gain a better intuition as to why it works.